In the final section of my chapter on Whitman, I will start by comparing John of the Cross with our poet. I am particularly inspired by these lines in John: And on my flowering breast / Which I had kept for him and him alone / He slept as I caressed / And loved him for my own. O guiding dark of night! / O dark of night more darling than the dawn! / O night that can unite / A lover and loved one, / Lover and loved one moved in unison.

I will put “negative theology” in conversation with queer theory, arguing that the “dark night,” a metaphor for depression, leads to a kind of self-emptying mystical experience. Whitman’s ascent to divinity amounts to “being averaged,” which is tantamount to a democratization of the body.

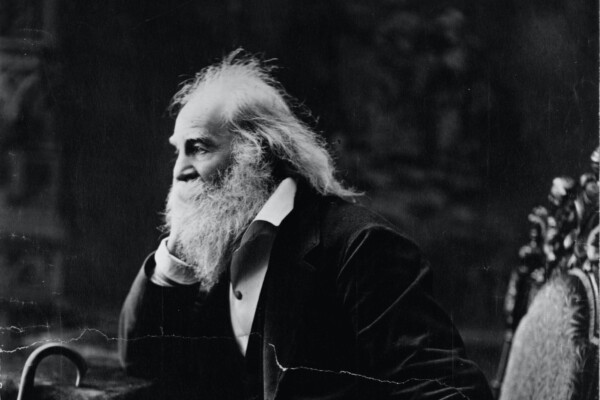

I then claim that the “Calamus” poems are examples of Deleuzian rhizomatic writing: “Like the ‘Live Oak, with Moss’ sequence, the ‘Calamus’ cluster does not tell a single story: it works paratactically, by juxtaposition and association, sprouting multiple, sometimes contradictory blossoms and leaves out of the breast of the poet’s man-loving heart” (Erkkila 118). Having described poems that become concerned with immanence, of going within, I argue that this connects to the mystical. It also marks the moment when Whitman becomes the very first existentially homosexual in modern literature: “Prior to Whitman there were homosexual acts but no homosexuals. Whitman coincides with and defines a radical change in historical consciousness: the self-conscious awareness of homosexuality as an identity” (51-2).

Here I share with you the opening lines, to be continued in further posts:

Were he to write his treatise on God, one might guess that Walt Whitman would take the cataphatic way. As we have seen before, Whitman finds God in everything, and should he tell us where to look, he would surely direct us to the underside of our bootsoles. This poetic commentary, of finding the miraculous in the everyday, is what makes Whitman “America’s Poet,” a poet of the everyday, and the every-man and -woman. Yet, as we have seen with “Live Oak, with Moss,” so much in Whitman depends on an unseen world. Famously, he says “When you read these [leaves] I that was visible am become invisible” (287). This invisibility is often understood to be a preoccupation with death and his ensuing artistic legacy. In Whitman’s inflated sense of the word, his legacy promises to mark the beginning of a new American aesthetic. So in some sense, his talk of the “seen and the unseen” reminds us that Whitman’s poetry reflected the spiritual promise of a nation.

In Whitman, we must accept that the queer aspect of his poetry, and the biographical details therein, remain somewhat shrouded in mystery. Writing just before the advent of the term “homosexual,” Whitman provides an affirming gay consciousness on the one hand, while on the other, provides a poetics of desire that signals something altogether different. The “Calamus” poems are examples of Deleuzian rhizomatic writing: “Like the ‘Live Oak, with Moss’ sequence, the ‘Calamus’ cluster does not tell a single story: it works paratactically, by juxtaposition and association, sprouting multiple, sometimes contradictory blossoms and leaves out of the breast of the poet’s man-loving heart” (Erkkila, “Manly Love” 118). Does it matter that this also becomes the moment when Whitman becomes the very first existentially homosexual in modern literature? We can reconcile these two ideas by understanding that Whitman was founding a psychology of loving men, one that was as noetic as it was physical; in other words, like the author itself, it often strikes its readers as quite contradictory.

As we have seen in John of the Cross’s poetry, there is an equal emphasis on the unseen and the theological component contained therein. In order to understand this, we must bear in mind John’s late medieval hermeneutic, one in which poetry was considered to have been an enhancement to prose commentaries. The idea of the night was not only an aesthetic choice for John; rather, the night represents the faith through which he seeks to live. In his commentary on “Dark Night,” John emphasizes the night’s passive nature. Though one must actively purge that which is abhorrent to the divine, ultimately one must remain passive to the divine. This work of purification is preparatory, and without it, the subject will not be ready for its promised divine union. John’s commentary only works through the first two stanzas of the eight sections of the poem. Though the work was left unfinished, these lines are dense enough to warrant an explanation…