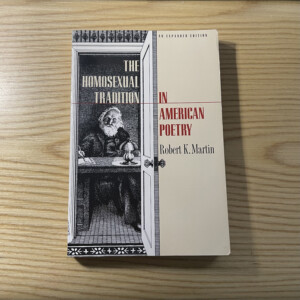

What goes on in the life of a Whitman researcher? Well, a lot of reading, that’s what! While there have been volumes upon volumes dedicated to the life and writings of Walt Whitman, none are more vital to my research than Robert K. Martin’s Homosexual Tradition in American Poetry. Published in 1979 amid a blossom of titles within the nascent “gay studies” discipline, Martin’s text is an oft-cited map for those of us reading Whitman as a father figure to queer poetry.

In Martin’s devastating and evocative words, “no one (since Virgil at least) had written, ‘He loves him’; instead they had written, ‘He loves her’ and ‘He kills him.’” (81). Though his point may be slightly hyperbolic, Martin’s point is that even when poets working in a Judeo-Christian tradition allow themselves to express same-sex desire, it is often in the form of a violent coming to blows. According to Martin, Whitman’s desire to love not only his fellow man, but everyone and every thing found in the world, connects him with queer writers such as Virginia Woolf. This is because Whitman’s epic Leaves of Grass breaks with the tradition, one that could be traced back to Virgil, of a single hero gone off to war. Whitman’s loafer is, quite simply, a collector of everything found in the world.

I’m eager to share more with you, but for now, allow me to part as Whitman ends his Calamus poem: